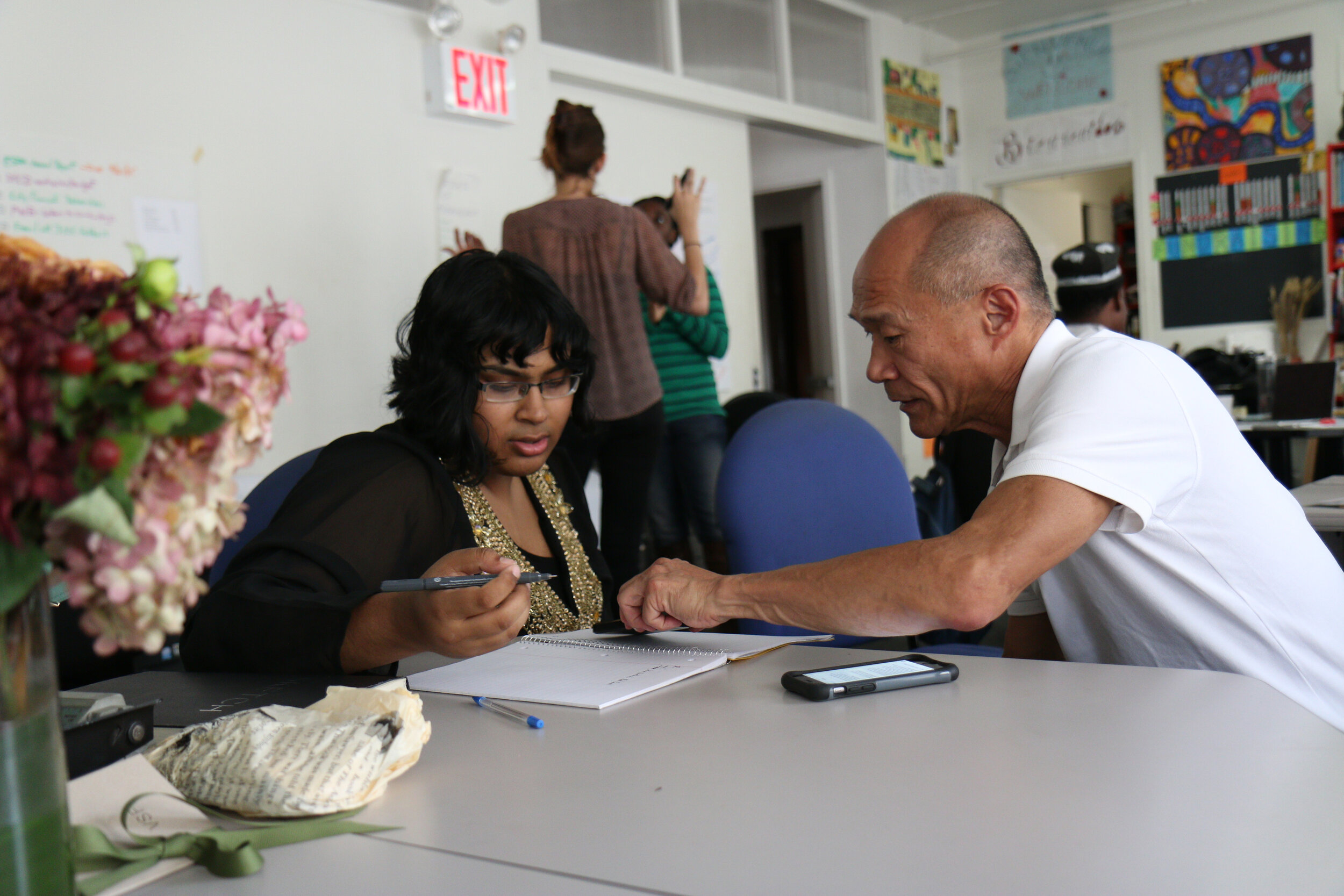

Mentorship v. Friendship at Work

You may have heard the saying, "If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together," but here's a similar axiom that is just as important: "If you want to be engaged at work, find a friend. If you want to perform better at work, find a mentor."

Many people will conflate career engagement with performance as well as friendship with mentorship. Yes, one of the more controversial Gallup poll questions found that people having a best friend at work leads to better performance; however, mentors are a more important variable in your career success.

Researchers at the University of Georgia identified three workplace competencies that predicted success: "knowing why," as in understanding your career motivation, personal meaning, and identification; "knowing how," as in your career-relevant skills and job-related knowledge; and "knowing whom," as in career-related networks and contacts, including relationships with others on behalf of the organization and personal connections.

An important variable in the "knowing whom" competency is mentoring relationships, which provide developmental experiences for individuals and valuable sources of learning. The researchers also wrote that mentors "provide access and visibility to protégés both directly, by exposing them to important people within and outside the organization, and indirectly, by providing challenging assignments."

Jonathan D. Green, president and CEO at Susquehanna University, also noted that mentoring relationships, particularly those outside your current institution, provide a system of checks and balances for higher education professionals.

"It's useful to establish a professional relationship with a person who has your job at another institution in a parallel-level position, because every once in a while we'll need a reasonableness check," Green said during a career advice panel discussion at the College and University Public Relations and Associated Professionals annual conference. "You need someone to have these conversations, which are always most effective when they are symbiotic relationships. It's a good way to frame things."

According to Green, "knowing whom" to select as a mentor should be lateral outside your college or university but upward within your institution.

"Ideally, in an organization (a mentor is) someone who's above you and it's someone whose job you don't want to have; not the I-want-your-job but the I-would-like-to-do-what-you-do," said Green, distinguishing between desiring someone's role and the way they approach their work. "A good senior colleague will almost always like to take advantage of an opportunity to pay forward what happened to them."

But how do you effectively pursue a mentor?

Here are a few tips:

1. Don't explicitly ask someone for their mentorship. Like any relationship, you need to develop it. A business doesn't ask you, "Do you want to be my customer?," otherwise, the arrangement becomes more transactional than relational.

2. Set a regular time to meet with your mentor, whether it's for coffee in the student union once a month, lunch at the annual conference, or tying an appointment to a cultural event that occurs each semester. College campuses are great for this, whether it's attending a basketball game, awards ceremony, or art exhibit, or volunteering together at an event like commencement.

3. Once you begin to understand each other and regularly share ideas, then set expectations that you consider the person a mentor and not as a friend because you want someone who will speak truth and "reasonableness" and not someone who will only tell you what you want to hear or make you feel good.

4. Finally, don't spend time with your mentor sharing war stories and venting about your job. Research, including a 2002 study where participants either hit a punching bag while looking at a critic or to become physically fit, has shown that the better you feel after venting the more aggressive you become, not only toward your critic but also toward innocent bystanders.

"When people vent their anger, they want to hit, scream, or shout, and it feels good to do that, and so they think, 'Oh, it feels good, it must work,'" venting study author Brad Bushman, professor of communication and psychology at Ohio State University, told SUCCESS Magazine. "But it also feels good to take street drugs and eat donuts. Just because something feels good, doesn't mean it's healthy."

Get a mentor you can count on.

The same approach applies to career health: it feels good to rely on friends, but it's great to have a mentor you can also rely on.

References: Hired Jobs, from an article by Justin Zackal